The Custom of the Country: Chapters 37-46

“She had worn black for a few weeks-not quite mourning, but something decently regretful…”

Are you ready to wrap up The Custom of the Country?

Have we all recovered from the shock of losing Ralph? Has Undine even noticed? I fear she’s moved on with her life without a thought for poor Ralph, may he rest in peace. With Ralph dead, Undine can marry Raymond, the Marquis de Chelles. She moves into his ancestral home, naively believing she will live a sophisticated life of European luxury. Once again, Undine will be disappointed by her choices, but we will discuss that shortly.

Let’s get into the final chapters of The Custom of the Country.

The final section begins with Paul arriving at the Hotel de Chelles. He feels overwhelmed by the change in his living situation and the sudden loss of his father. The hotel is grander and more intimidating than the home he knew in New York.

“In a drawing-room hung with portraits of high-nosed personages in perukes and orders, a circle of ladies and gentlemen, looking not unlike every-day versions of the official figures above their heads, sat examining with friendly interest a little boy in mourning.”

Meanwhile, it is also clear that Undine has no idea how to be a mother to Paul. She displays no empathy for his situation and expects him to listen to her almost like a well-trained pet. When he doesn’t, she complains about how “they” (Ralph’s family) have turned him into a “savage.” Thankfully, Raymond comes to Paul’s rescue and will become a father figure to him. To Undine’s great annoyance, Raymond expects her to act toward Paul like any good French mother would.

“Undine, at first, was somewhat dismayed to find that she was expected to fit the boy and his nurse into a corner of her contracted entresol. But the possibility of a mother's not finding room for her son, however cramped her own quarters, seemed not to have occurred to her new relations, and the preparing of her dressing-room and boudoir for Paul's occupancy was carried on by the household with a zeal which obliged her to dissemble her lukewarmness.”

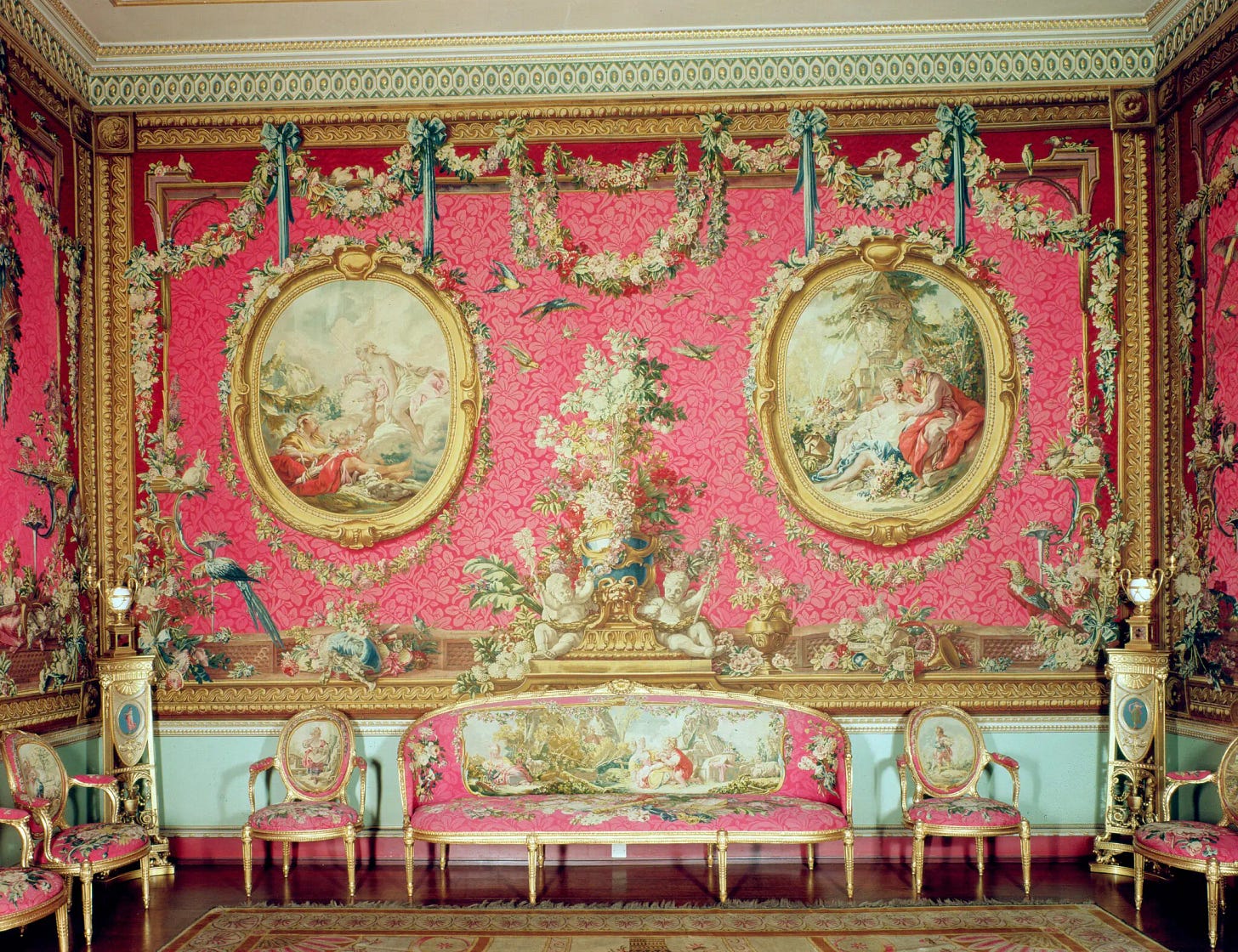

Undine’s disillusionment doesn’t end with motherhood. She also discovers that titles and estates don’t equal money. She expects to be the mistress of Hotel de Chelles, only to find that she and Raymond are expected to live in his rather small bachelor apartment while the rest of the house is rented to “old-fashioned tenants.” This situation is common for many aristocratic families. They may have large ancestral homes filled with treasures, but they no longer have the funds to maintain the lavish lifestyles of past generations. Undine hopes she can convince Raymond to adopt a more modern way of living, but this will prove to be quite the challenge.

Undine is also surprised that Raymond is a jealous and controlling husband. “None of the men who had been in love with her before had been so frankly possessive, or so eager for reciprocal assurances of constancy.” At first, she finds this jealousy intriguing. It gives her “a keener sense of recovered power.” Undine loves to be desired and misinterprets jealousy as love and devotion. She will soon realize how badly she has misunderstood Raymond.

“Raymond seemed to attach more importance to love, in all its manifestations, than was usual or convenient in a husband; and she gradually began to be aware that her domination over him involved a corresponding loss of independence. Since their return to Paris she had found that she was expected to give a circumstantial report of every hour she spent away from him. She had nothing to hide, and no designs against his peace of mind except those connected with her frequent and costly sessions at the dress-makers', but she had never before been called upon to account to any one for the use of her time, and after the first amused surprise at Raymond's always wanting to know where she had been and whom she had seen she began to be oppressed by so exacting a devotion. Her parents, from her tenderest youth, had tacitly recognized her inalienable right to "go round," and Ralph though from motives which she divined to be different had shown the same respect for her freedom. It was therefore disconcerting to find that Raymond expected her to choose her friends, and even her acquaintances, in conformity not only with his personal tastes but with a definite and complicated code of family prejudices and traditions…”

Undine wants to return to her life of fun with her Parisian friends, like Princess Estradina and the other American expats, but that’s not what is expected of the wife of Raymond de Chelles. Undine’s brash Americanness begins to drive a wedge between her and Raymond. This divide is so noticeable that Madame de Trézac, a friend from Undine’s past, warns her:

“My dear, a woman must adopt her husband's nationality whether she wants to or not. It's the law, and it's the custom besides. If you wanted to amuse yourself with your Nouveau Luxe friends you oughtn't to have married Raymond -but of course I say that only in joke. As if any woman would have hesitated who'd had your chance! Take my advice keep out of Lili's set just at first. Later ... well, perhaps Raymond won't be so particular; but meanwhile you'd make a great mistake to go against his people:"

But when has Undine ever listened to anyone’s advice? She wants what she wants, and she’ll get it however she can. She does not give a fig about tradition or social customs.

Another shocking revelation for Undine is her realization that she must negotiate (read: beg) for an allowance from Raymond. She manages to get him to agree to $5,000 for “the bringing up and education of her son,” but anything else needs to come from the money she receives from Mr. Spragg. Undine is frankly flabbergasted. “She did not understand how a man so romantically in love could be so unpersuadable on certain points.” Ralph never tried to control her to this degree! Even Peter let her have whatever she wanted.

“The money was hers, of course; she had a right to it, and she was an ardent believer in "rights." But she wished she could have got it in some other way she hated the thought of it as one more instance of the perverseness with which things she was entitled to always came to her as if they had been stolen.”

She is used to spending her money however she likes and doing whatever she wants. When she faced resistance in the past, she could throw a fit and have her way. It seems she may have met her match in Raymond. He deeply respects tradition and his position in society and will not tolerate Undine’s frivolous behavior. This might be the first time anyone has tried to control her to this degree. Undine resents having to grovel for things she believes she’s entitled to, such as as much money as she desires. Slowly, their marriage becomes a battle of wills.

To make matters worse for Undine, Raymond decides that their time in Paris has ended and moves his household to their country house, the Château de Saint Desert. Raymond knows he can’t trust his new wife in the glittering lights of Paris, but it’s also a tradition for the family to retreat to the countryside for most of the year.

“When, the year before, she had reluctantly suffered herself to be torn from the joys of Paris, she had been sustained by the belief that her exile would not be of long duration. Once Paris was out of sight, she had even found a certain lazy charm in the long warm days at Saint Désert. Her parents-in-law had remained in town, and she enjoyed being alone with her husband, exploring and appraising the treasures of the great half-abandoned house, and watching her boy scamper over the June meadows or trot about the gardens on the pony his stepfather had given him…She was the more resigned to this interlude because she was so sure of its not lasting.”

These idyllic days in the country soon begin to grate on her. She continues to spend money as if she has an endless supply. Bored, she can’t stop purchasing dresses and other unnecessary trifles. Raymond grows tired of her extravagance and tries to reason with her, standing his ground despite Undine’s attempts to manipulate him.

“She was beginning to see that he felt her constitutional inability to understand anything about money as the deepest difference between them. It was a proficiency no one had ever expected her to acquire, and the lack of which she had even been encouraged to regard as a grace and to use as a pretext, During the interval between her divorce and her remarriage she had learned what things cost, but not how to do without them; and money still seemed to her like some mysterious and uncertain stream which occasionally vanished underground but was sure to bubble up again at one's feet.”

Undine keeps herself almost willfully ignorant of how the world works. She thinks she can continue as she always has—partying, shopping, and doing what she likes—but Raymond is having none of it. He has expectations for his wife and insists that Undine meet them. Unfortunately, even Raymond can only tolerate Undine’s childishness for so long.

“After that, she noticed, though he was as charming as ever, he behaved as if the case were closed. He had apparently decided that his arguments were unintelligible to her, and under all his ardour she felt the difference made by the discovery. It did not make him less kind, but it evidently made her less important; and she had the half-frightened sense that the day she ceased to please him she would cease to exist for him.”

Undine recognizes how her behavior could lead to her falling out of Raymond’s good graces, yet she fails to heed these concerns and adjust her actions. Ultimately, a few significant transgressions cause Raymond to lose interest in his beautiful wife.

One is Undine’s vocal disapproval of Raymond renting the Hotel de Chelles to his brother Hubert’s soon-to-be father-in-law. Raymond agrees to this plan because Hubert is marrying a wealthy American heiress. He rented the Hotel on the condition that his new American in-laws modernize the home. Undine is outraged at the idea of sharing her home with Hubert (I don’t blame her; he sounds like a drunk loser), but also at no longer being the only American “heiress” in the family. Undine is a jealous creature. She refuses to live in the Hotel again. But of course, this tantrum is all bark and no bite. Ultimately, she moves back into her old apartments at the Hotel.

“Their outward relations had not changed since her outburst on the subject of Hubert's marriage. That incident had left her half-ashamed, half-frightened at her behaviour, and she had tried to atone for it by the indirect arts that were her nearest approach to acknowledging herself in the wrong. Raymond met her advances with a good grace, and they lived through the rest of the winter on terms of apparent understanding.

When the spring approached it was he who suggested that, since his mother had consented to Hubert's marrying before the year of mourning was over, there was really no reason why they should not go up to Paris as usual; and she was surprised at the readiness with which he prepared to accompany her.”

Another mark against Undine arises from her disinterest in Raymond’s advances. When they first retreat to the country, Undine is surprised by Raymond’s insistence on spending time with her instead of indulging in his own pursuits. He wants to spend his evenings reading to her and discussing books and art. He’s a cultured man eager to share his passions with his wife and connect with Undine on an intellectual level. Unfortunately for Raymond, Undine has no time for such trivial matters. She finds his attempts to connect with her boring. She prefers life in Paris because they’re both too busy with their own affairs to bother each other.

“But once back in Paris she had less time for introspection, and Raymond less for books. They resumed their dispersed and busy life, and in spite of Hubert's ostentatious vicinity, of the perpetual lack of money, and of Paul's innocent encroachments on her freedom, Undine, once more in her element, ceased to brood upon her grievances. She enjoyed going about with her husband, whose presence at her side was distinctly ornamental.”

At first, Undine relishes the freedom Raymond allows her when they’re in Paris. But soon she can’t ignore his growing disinterest. She initially thinks it’s related to their not having a child of their own. Especially after discovering that Hubert’s wife is pregnant soon after their marriage. She brings this up to Raymond, but he brushes her off with a hollow compliment:

"Your mother blames me for our not having a child. Everybody thinks it's my fault."

"My mother's ideas are old-fashioned; and I don't know that it's anybody's business but yours and mine."

"Yes, but—"

"Here we are." The brougham was turning under the archway of the hotel, and the light of Hubert's tall windows fell across the dusky court. Raymond helped her out, and they mounted to their door by the stairs which Hubert had recarpeted in velvet, with a marble nymph lurking in the azaleas on the landing.

In the antechamber Raymond paused to take her cloak from her shoulders, and his eyes rested on her with a faint smile of approval.

"You never looked better; your dress is extremely becoming. Good-night, my dear," he said, kissing her hand as he turned away.

He leaves her at home and goes off on his nightly adventures. Undine finally recognizes that she is losing him. When he suggests returning to the country, she agrees without hesitation. She hopes to regain his attention upon their return, but they only grow further apart. It’s not just the distance between her and Raymond that troubles her. She is also realizing how painfully repetitive and boring her life is and will always be as long as she is Raymond’s wife.

“The days crawled on with a benumbing sameness. The old Marquise and the other ladies of the party sat on the terrace with their needle-work, the cure or one of the visiting uncles read aloud the Journal des Débats and prognosticated dark things of the Republic, Paul scoured the park and despoiled the kitchen-garden with the other children of the family, the inhabitants of the adjacent châteaux drove over to call, and occasionally the ponderous pair were harnessed to a landau as lumbering as the brougham, and the ladies of Saint Désert measured the dusty kilometres between themselves and their neighbours.

It was the first time that Undine had seriously paused to consider the conditions of her new life, and as the days passed she began to understand that so they would continue to succeed each other till the end. Every one about her took it for granted that as long as she lived she would spend ten months of every year at Saint Désert and the remaining two in Paris.”

Her monotonous life in the country is finally interrupted when Princess Estradine arrives for an unannounced visit. Raymond is away, and his mother receives the surprise guests out of familial duty. Undine relishes this unexpected change in pace, marking the first bit of excitement she has had in many weeks. The Princess remarks:

“My dear, you're handsomer than ever; only perhaps a shade too stout. Domestic bliss, I suppose? Take care! You need an emotion, a drama... You Americans are really extraordinary. You appear to live on change and excitement; and then suddenly a man comes along and claps a ring on your finger, and you never look through it to see what's going on outside. Aren't you ever the least bit bored? Why do I never see anything of you any more?"

The Princess asks why Undine allows herself to be cooped up in the country. She says it’s because Raymond is jealous, but the Princess scoffs. If Raymond is away having his own fun, why shouldn’t Undine as well?

“Politics don't occupy a man after midnight. Raymond jealous of you? Ah, merci! My dear, it's what I always say when people talk to me about fast Americans: you're the only innocent women left in the world...”

We’re beginning to see, as is Undine, that American and European values do not mix. Undine embodies New American values, which stand in stark contrast to European beliefs. She will never fit into her new life and family if she doesn’t adopt European ways. However, we, the readers, understand that Undine lacks the capacity for personal growth. These domestic culture wars have taken their toll on the marriage, which continues to deteriorate. Her mother-in-law seems to be avoiding her, and Raymond cares less and less about how she spends her time. Meanwhile, Undine is suffocating under the monotony of her life.

“She knew she was spending too much money, and she had lost her youthful faith in providential solutions; but she had always had the habit of going out to buy something when she was bored, and never had she been in greater need of such solace.

The dullness of her life seemed to have passed into her blood: her complexion was less animated, her hair less shining. The change in her looks alarmed her, and she scanned the fashion-papers for new scents and powders, and experimented in facial bandaging, electric massage and other processes of renovation.”

She has no hobbies, interests, or depth of character. She lives to be admired and to have fun. But when this is taken from her, Undine begins to wither. At the same time, Raymond pulls further away from her, and she starts to wonder if he’s having an affair.

“Undine did not believe that her husband was seriously in love with another woman she could not conceive that any one could tire of her of whom she had not first tired but she was humiliated by his indifference, and it was easier to ascribe it to the arts of a rival than to any deficiency in herself.”

With the Princess’s words swimming in her ears, Undine decides to have some fun. However, Raymond confronts Undine when she plans to go to Paris to stay with her American friends without him. He gives her a speech about the impropriety and excessive expense of her plan. They argue about money, revealing once again how Raymond values heritage and tradition, while Undine only cares about enjoying everything shiny and new. She pushes Raymond over the edge when she suggests they could sell their country home to solve all their cash flow issues.

"I understand that you care for all this old stuff more than you do for me, and that you'd rather see me unhappy and miserable than touch one of your great-grandfather's arm-chairs."

Raymond stands firm on his beliefs and traditions, throwing Undine for a loop. She is so used to manipulating a situation to her advantage with an outburst that she can’t believe her tried-and-true tactics don’t work on Raymond.

“The incident left Undine with the baffled feeling of not being able to count on any of her old weapons of aggression. In all her struggles for authority her sense of the rightfulness of her cause had been measured by her power of making people do as she pleased Raymond's firmness shook her faith in her own claims, and a blind desire to wound and destroy replaced her usual business-like intentness on gaining her end. But her ironies were as ineffectual as her arguments, and his imperviousness was the more exasperating because she divined that some of the things she said would have hurt him if any one else had said them: it was the fact of their coming from her that made them innocuous. Even when, at the close of their talk, she had burst out: "If you grudge me everything I care about we'd better separate," he had merely answered with a shrug: "It's one of the things we don't do " and the answer had been like the slamming of an iron door in her face.”

While Undine broods over how to break Raymond from his “selfish folly,” she receives a surprise visit from none other than Elmer Moffatt. He arrives in a motor car with an art dealer in tow. He claims he’s there to look at some very old and valuable tapestries that have been in Raymond’s family for generations. However, he’s really there to show Undine that he has finally made it. Moffatt soon sends the dealer packing so he can spend time alone with Undine.

"I suppose you must be awfully rich."

He laughed too, holding her eyes. "Oh, out of sight!”

He asks her why she is shut up in the country instead of living it up in Paris. She explains that Raymond is busy with the estate, but more importantly, they cannot afford it. Moffatt responds:

“Well, that sounds aristocratic; but ain't it rather out of date? When the swells are hard-up nowadays they generally chip off an heirloom." He wheeled round again to the tapestries. “There are a good many Paris seasons hanging right here on this wall.”

And finally, someone is speaking Undine’s language. Being with Moffatt gives Undine a much-needed confidence boost.

“Here was some one who spoke her language, who knew her meanings, who understood instinctively all the deep-seated wants for which her acquired vocabulary had no terms; and as she talked she once more seemed to herself intelligent, eloquent and interesting.”

Meanwhile, Hubert’s wife is about to give birth, leaving Undine in charge of reopening the Hotel de Chelles for the season. But once again, Undine finds herself battling against tradition. Her mother-in-law allows her and Raymond to spend two months in Paris, with conditions, the most important of which is that they must “exercise the most unremitting economy.” Undine wants to host parties and live it up, but dinners are too expensive for their meager budget.

The couple are butting heads over entertaining, when a dunning letter arrives, sending Raymond over the edge. He confronts Undine, insisting she pay her own bills. She can’t understand why she should when he always paid her bills in the past.

“But it was impossible for Undine to understand a social organization which did not regard the indulging of woman as its first purpose, or to believe that any one taking another view was not moved by avarice or malice; and the discussion ended in mutual acrimony.”

Undine takes it upon herself to contact the dealer who came with Moffatt about possibly selling the tapestries. When Raymond receives Moffatt’s offer, he is livid. He is finally done with his wife and cannot believe Undine would try to sell his heritage.

"And you're all alike," he exclaimed, "every one of you. You come among us from a country we don't know, and can't imagine, a country you care for so little that before you've been a day in ours you've forgotten the very house you were born in—if it wasn't torn down before you knew it! You come among us speaking our language and not knowing what we mean; wanting the things we want, and not knowing why we want them; aping our weaknesses, exaggerating our follies, ignoring or ridiculing all we care about-you come from hotels as big as towns, and from towns as flimsy as paper, where the streets haven't had time to be named, and the buildings are demolished before they're dry, and the people are as proud of changing as we are of holding to what we have and we're fools enough to imagine that because you copy our ways and pick up our slang you understand anything about the things That make life decent and honourable for us!"

[Insert Applause]

Undine is shocked. No one has ever scolded her like this, especially not a man. She doesn’t understand why he’s so angry. To her, it’s all relatively simple. Why economize when you can sell off some old family treasures and remain solvent? Undine might like nice things, but she doesn’t respect them. Her life is about consumption, not preserving the past.

With Raymond washing his hands of her, Undine finds herself daydreaming about Apex and her courtship with Elmer. She can’t get him (and his new wealth) out of her mind. She calls him and arranges a meeting. This meeting turns into many. Undine finds camaraderie with Moffatt. They understand each other, and it doesn’t hurt that he’s now very, very rich.

“He used life exactly as she would have used it in his place. Some of his enjoyments were beyond her range, but even these appealed to her because of the money that was required to gratify them.”

She continues to meet with Moffatt, falling increasingly in love with the idea of him. At the same time, Raymond distances himself from Undine. Even her mother-in-law gives her the cold shoulder. She becomes more disenchanted with her life as Raymond’s wife. When she can no longer endure it, she runs to Moffatt for help.

“She did not think of Moffatt as a power she could use, but simply as some one who knew her and understood her grievance. It was essential to her at that moment to be told that she was right and that every one opposed to her was wrong.”

When she arrives at his hotel room in distress, he listens to her, comforts her, and treats her as she wished Ralph and Raymond would have. Moffatt finally has Undine where he wants her. He has been climbing the social ladder, trying to win her back for years, and it is finally time for him to claim his reward.

“…you were my wife once, and you were my wife first-and if you want to come back you've got to come that way: not slink through the back way when there's no one watching, but walk in by the front door, with your head up, and your Main Street look."

Undine wants to run away with Moffatt but feels trapped in her marriage to Raymond. She fears she won’t be able to divorce Raymond because the Catholic Church doesn’t allow it. However, Moffatt is confident he can arrange it. She needs to trust him to handle everything (is there anything money can’t buy?). He has worked too hard for too long to give up his chance at winning Undine back.

"See here, Undine," he said slowly, as if he measured her resistance though he couldn't fathom it, "I guess it had better be yes or no right here. It ain't going to do either of us any good to drag this thing out. If you want to come back to me, come-if you don't, we'll shake hands on it now. I'm due in Apex for a directors' meeting on the twentieth, and as it is I'll have to cable for a special to get me out there. No, no, don't cry—it ain't that kind of a story ... but I'll have a deck suite for you on the Semantic if you'll sail with me the day after tomorrow."

Moffatt secures a divorce for Undine and remarries her. Once again, Paul has a new father. When we next see him, Paul wanders through an empty hotel in Paris. His mother and Moffatt are married and constantly travel between New York, Paris, and Rome, wherever Undine wishes to go. Paul is left in the care of an aging Mrs. Heeny. Poor, neglected Paul feels confused and seeks to learn more about his life, his father, and, of course, his mother. Mrs. Heeny reads her clippings about his parents’ travels and all the new things they’ve acquired for Moffatt’s collections. However, Paul doesn’t want to hear about their purchases; he wants to know about his mother. The poor boy is adrift, with no anchor. He is hurt by all the terrible things his mother said about Raymond during the divorce trial. He cares deeply for his French father, who stepped up and tried to fill the void left by the father he lost. It’s heartbreaking to learn that he barely remembers Ralph.

To Moffatt’s credit, he tries to step in and be a parent to Paul because Undine still doesn’t have time for him.

"If we two chaps stick together it won't be so bad—we can keep each other warm, don't you see? I like you first rate, you know; when you're big enough I mean to put you in my business. And it looks as if one of these days you'd be the richest boy in America..."

Moffatt may have the best intentions toward Paul, but he fails to realize that Paul desires affection and a stable family life, similar to what he experienced with the Marvells. Unlike his mother, he doesn’t care about money and luxurious possessions.

We end with a final look at Undine. Undine is still unsatisfied despite having everything she ever wanted, money and the freedom to do as she pleases.

“But under all the dazzle a tiny black cloud remained. She had learned that there was something she could never get, something that neither beauty nor influence nor millions could ever buy for her. She could never be an Ambassador's wife; and as she advanced to welcome her first guests she said to herself that it was the one part she was really made for.”

Undine remais as insatiable as ever. How long will she stay with Moffatt before she trades him in for someone new?

I have a few final points before we say goodbye to The Custom of the Country:

American vs. European Values:

Undine Spragg embodies the quintessential American values of the period: relentless ambition, social climbing, and the belief that everything can be bought for the right price. Her constant pursuit of higher social status reflects the American dream of unlimited upward mobility. However, in The Custom of the Country, Wharton demonstrates how such unbridled ambition can lead to moral bankruptcy and personal isolation. Undine continues to climb but never finds satisfaction in her life. Even surrounded by everything she ever wanted, she finds something new to covet.

In contrast, Raymond de Chelles and his family embody European values. They represent a world of established traditions, cultural refinement, and rigid social hierarchies. They prioritize family history, artistic appreciation, and social obligations. These values oppose American pragmatism and innovation, which are represented by characters like Undine and Elmer Moffatt.

In this novel, Wharton particularly emphasizes the European view of marriage as a social institution that serves family and societal interests rather than individual desires. This contrasts sharply with the American conception of marriage as something that can be entered and exited at a whim. We see this in all the ways Raymond and Undine butt heads throughout their marriage. The American preference for material comfort over historical significance is evident in Undine's inability to appreciate the cultural heritage of Saint Désert and her constant desire for modern luxuries. She will never acquire the deep understanding and appreciation of culture and tradition that her European in-laws naturally possess.

They may share a common language, but they do not understand each other. In fact, it’s more accurate to say that Raymond understands Undine, but she doesn’t care to understand her husband or his culture. Her relentless ambition blinds her to much and dooms their relationship from the start.

Sargent's Madame X:

John Singer Sargent's portrait of Madame X (1883-1884) is one of the most controversial paintings of the late 19th century. The portrait depicts Madame Pierre Gautreau (née Virginie Amélie Avegno), an American expatriate known for her striking beauty and sophisticated presence in Parisian social circles. The portrait provoked immediate scandal when it was unveiled at the Paris Salon of 1884. The public reaction was so severe that Madame Gautreau's reputation suffered significantly, and Sargent was forced to retreat from Paris to London, where he would eventually rebuild his career.

What made the painting so controversial was the subject's revealing dress, with one strap provocatively slipping from her shoulder in the original version. Moreover, Madame Gautreau's pose, turned away from the viewer with her profile emphasized, her haughty expression, and exposed décolletage were seen as overtly sensual and inappropriately bold for a woman of her social standing. The painting seemed to embody what conservatives viewed as the moral decay of modern society.

I can’t help but draw comparisons between Undine Spragg and Madame X. They are both American women attempting to conquer Parisian society, and both became subjects of scandal due to their ambition and how they present themselves. It wouldn’t surprise me to find out that the character of Undine Spragg was inspired, at least in part, by Madame Gautreau. There are remarkable parallels between the women:

Both women were known for their striking beauty and used it as a form of social currency.

Both understood the power of public appearance and carefully crafted their images to maximize their social impact.

Both transgressed social boundaries, violated conventions, and are scandalized.

The reactions of French society to both women reveal interesting parallels about the cultural tensions between American and European sensibilities. Just as Madame Gautreau's portrait was deemed too bold and provocative for French tastes, Undine's American approach to marriage and social climbing was regarded as vulgar and inappropriate by the traditional French aristocracy.

I included a copy of Manet’s La Parisienne for context. This is what a respectable, married Parisienne lady was meant to be. She is demure and sophisticated—two things no one has ever accused Undine of being.

If you’re in New York City and want to learn more about Madame X and Sargent, the Metropolitan Museum of Art is currently showing a wonderful Sargent in Paris exhibit (it runs through August 3). If you can’t get to the city, the curators have a video walk-through of the exhibit. I’m curious to hear if any of you also made a connection between Madame X and Undine. Let me know in the comments.

The American Dollar Princesses:

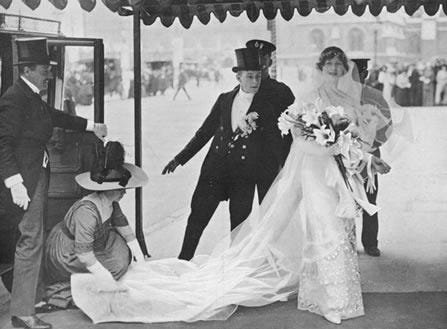

The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw the rise of the "Dollar Princesses." Wealthy American heiresses married into European nobility, exchanging New World money for Old World titles. Undine could be considered one of these women, but the true Dollar Princess is her brother-in-law’s young American wife.

American heiresses brought with them not only their wealth but also diverse social attitudes, modern perspectives, and a certain entrepreneurial spirit. These women and their money played crucial roles in modernizing and preserving great European estates, introducing new American innovations and management techniques. They installed indoor plumbing, central heating, and even electricity. Many European estates were crumbling and financially underwater. New Money Americans provided much-needed cash injections in exchange for titles and social credibility they couldn’t find at home.

Like many actual American heiresses of the Gilded Age, Undine sees European aristocracy as the ultimate prize in her social climbing endeavors. Wharton presents Undine as perpetually unsatisfied and unable to truly assimilate into European society. Despite their wealth, many American heiresses found it challenging to adapt to the aristocratic society of Europe, much like our heroine, Undine. They were often regarded as vulgar newcomers, and nothing in America prepared them for the complex social codes, rigid class structures, and differing cultural expectations of their new lives.

There are numerous videos, articles, and books about The Dollar Princesses. I particularly enjoy The Gilded Heiress YouTube Channel, which features many videos about these women if you want to learn more. Wharton wrote her Dollar Princess novel, The Buccaneers, which was completed after her death. I haven’t included it in this reading project, but I encourage you to read it when you can. I believe she does a wonderful job of highlighting the excitements and disappointments these women experienced.

Final Thoughts:

What did you think of Undine? Did you like her? Did you hate her? What about Moffatt? Did he grow on you as the novel progressed? What do you think Wharton wants us to take away from reading The Custom of the Country? Is she perhaps too critical of America and its new moneyed class? Did you find anything romantic in his pursuit of Undine?

Our next read, Twilight Sleep, started on May 1. I hope you can join me. I will post my thoughts on Book One soon, so be sure to subscribe so you don’t miss a post!

As always, I’m looking forward to our next discussion, and thank you so much for reading along with me.

Happy Reading!

While reading Hermione Lee’s biography of Edith Wharton, I learned that both “The House of Mirth” and “The Custom of the Country” were originally published in serial form in “Scribner’s Magazine”, a monthly periodical issued by Wharton’s publisher, Charles Scribner and Sons. Only later did Scribner release the novel format editions of “The House of Mirth” and “The Custom of the Country”. It occurred to me that it was highly likely that Edith Wharton would have revised the serial installments of her stories when putting them into single volume form, likely editing them down to some degree.

Sure enough, in her lengthy discussion of “The Custom of the Country”, Hermione Lee describes how Wharton made “minute, but continual” revisions in her text when preparing for its publication as a novel, “all in the interests of toning-down any romantic magazine touches and making the whole thing drier.” Lee then gives examples of lines of dialogue that Wharton excised in creating her final version of the story.

Perhaps some publishing firm has already done it, but it would be interesting to read the monthly serial installments of “The House of Mirth” and “The Custom of the Country” side-by-side with their novel versions in one volume. Or perhaps editions of the novels could be published with the material from the serial versions included in square brackets or a different type of font. In any case, it would be fascinating to read these two novels in the form in which Edith Wharton originally imagined them, and see what portions of them she thought could be shorn away in putting them into single-volume format.

In other news, it seems that the "Miss Austen" mini-series was so popular that a follow-up series, "Miss Austen Returns" is under development.

On the whole, I found “The Custom of the Country” to be a more satisfying novel than “The House of Mirth”, mainly because Wharton requires less emotional engagement from me as a reader. Not that there’s anything wrong with feeling connected to a fictional character, but in the case of Lily Bart, she comes across as more of a figure in a morality tale than a flesh-and-blood human being in a realistic novel. The same goes for the other characters in “The House of Mirth”. For example, there’s the scene early in the novel where Lily and Lawrence are alone together outside on a beautiful September afternoon amidst the lush gardens of the Bellomont estate. They’re obviously attracted to each other, and talk at length about their respective views of life. It’s apparent that this is the sort of personal, self-revelatory conversation they can have with no-one but each other. But nothing happens. The mood is broken for Lily when a car drives by, and Lawrence passively sits back and lets her recollect her agenda for the afternoon, which involved snaring Percy Gryce as her husband, though she’s unwittingly already squandered her chances with him. In the plot Edith Wharton has designed, every door for Lily is slammed shut before she gets to it, and nothing can prevent her from dying in the final chapter.

It's the same with the ending of the novel. Even though Lily has shown absolutely no maternal instincts throughout the rest of the story, we now see her comforting herself by cradling an imaginary infant in her arms during her dying moments. Here, I think, Wharton was really laying on the mawkish sentimentality pretty thick. It’s not that the scene isn’t effectively written, and you admire how skillfully Wharton elicits our sympathy for Lily, but I had the same feeling of being in the hands of a master manipulator as when I saw Steven Spielberg’s “E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial” for the first time.

Undine Spragg, on the other hand, is the anti-Lily Bart. We don’t feel any sympathy for her, and to be honest, she doesn’t ask for any. Without any emotional engagement in Undine, we are free to observe her throughout the novel in a detached manner. We do feel badly for Ralph Marvell, but his impulsive suicide seems indicative of a man with the same inner weakness and lack of resolution that prevents Lawrence Selden from intervening to help Lily Bart until it is too late. As for Ralph’s son, Paul, his mother may not be interested in him, but there is every reason to expect that his stepfather, Raymond de Chelles, and even Elmer Moffat, will give him the parental care and affection that Undine seems incapable of showing her only child. In terms of material care and comfort, at least, we can be assured Paul will lack for nothing.

I also liked the way “The Custom of the Country” ended without a resolution or final decision about Undine Spragg, so unlike Lily Bart in “The House of Mirth”. Wharton concludes her story on a realistic, true-to-life, ambiguous note. We sense that Undine will go on with her life, continuing to be dissatisfied with her lot, because she’s never paused to reflect upon what is really important to her. She has no core values or personal relationships to cling to and provide a foundation for a settled life. Undine will always be adrift in a society that will continue to change around her.